Two Weeks in Timor

A Political Travelogue

By Eric S. PiotrowskiPhotos by ESP, Diane Farsetta, and John Peck

|

"To resist is to win." Xanana Gusmão

|

In 2005 I visited East Timor with my special lady friend Diane Farsetta (now my wife) and the farming activist John Peck (now my friend). I wrote the following piece after we returned and printed up copies to hand out. I kept meaning to put it on the web, but for whatever reason I never did.

Until today (22 June 2016).

Enjoy, and please visit etan.org to get involved in the continuing struggle for East Timor. Also visit aideasttimor.org for information about solidarity work in Dane County, Wisconsin.

Contents

- Preface: Why I Went

- Part One: With My Own Eyes

- Part Two: Dili, The City

- Part Three: Ainaro (The Past Didn't Go Anywhere)

- Part Four: Korean Air & Seoul (A Dream of Baduk Deferred)

- Part Five: Conclusions

Preface: Why I Went

In 1991, at the time of "Operation Desert Storm", I read an interesting article in Utne Reader headlined "What About East Timor?" The author asked: If the Bush administration was so keen on enforcing UN resolutions and keeping nations from invading their smaller neighbors, why didn't we stand up to Indonesia and do something about its brutal occupation of East Timor? I didn't know it at the time, but that half-page article changed my life.

I shan't delve into the history of East Timor here, since many people who read this already know about it; and those who don't can find the information easily enough. The Wikipedia article Indonesian occupation of East Timor is a good start, and Matthew Jardine's slim volume Genocide in Paradise is perhaps the best introductory text available. (I also recorded a podcast with visual aids.)

I shan't delve into the history of East Timor here, since many people who read this already know about it; and those who don't can find the information easily enough. The Wikipedia article Indonesian occupation of East Timor is a good start, and Matthew Jardine's slim volume Genocide in Paradise is perhaps the best introductory text available. (I also recorded a podcast with visual aids.)

In college, I read several books about East Timor and learned about the history of that nation, including — to my horror — the US government's decades-long support for the slaughter Indonesia was carrying out (where at least 100,000 people were killed through army massacre and enforced starvation). This was part of a much larger awakening I underwent to the ugly truths of the world, and I had trouble coming to terms with the horrors I found around every corner. But something unique stood out in the struggle of the Timorese people.

Part of it was the commitment to nonviolence. The resistance had an armed component: Falintil, the military sector of the leading political party, Fretilin. But overwhelmingly, the people of Timor Loro Sae (as it is called in the indigenous language, Tetun) pursued a nonviolent strategy appealing to justice, democracy, and international law. They realized that an all-out war would likely lead to more death and suffering in the long run. In 1996, two of the resistance leaders, José Ramos-Horta and Bishop Carlos Ximines Belo, won the Nobel Peace Prize for their nonviolent efforts to end the occupation.

I was also shocked and repulsed by my government's complicity in the bloodshed. The day before Indonesia invaded, President Gerald Ford and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger went to Jakarta and, witnesses said, "gave the green light" for the invasion. In all, the United States of America — a nation which had always stood up for democracy and justice, according to my history teachers — provided over one billion dollars in weapons and equipment to the Indonesian military during the 25 years of East Timor's nightmare.

Even when East Timor was finally allowed to vote in a referendum on independence supervised by the United Nations in 1999, the United States stood by and watched while Indonesian-sponsored militias tore the country apart one last time. (Thousands were killed and 70% of the buildings were destroyed after East Timor voted for indpendence.) When a reporter asked Clinton's National Security Advisor, Sandy Berger, whether we had an obligation to do something about the violence in East Timor (given our recent intervention in Kosovo), he replied: "[My daughter] has a very messy apartment up in college. Maybe I shouldn't intervene to have that cleaned up."

The other reason I became so interested in East Timor was that it seemed to be a clear-cut case of right and wrong. Not only was Indonesia wrong for occupying an independent nation (while Portugal was the colonial power in East Timor, Indonesia said they had no claim to it); but our government was clearly wrong for supporting such atrocities. Eventually I realized that I couldn't in good conscience know about East Timor's suffering and not take action.

Before long, I was an active volunteer with the East Timor Action Network, developing the Florida chapter of ETAN and serving as layout editor for Estafeta, its national newsletter. As I organized speaking events, conducted letter-writing campaigns, and spread the word in every way possible, I found myself falling deeply in love with this land I had never seen for myself. I met many people from East Timor; their resilience, intelligence, and commitment to peaceful activism served as a powerful inspiration.

Before long, I was an active volunteer with the East Timor Action Network, developing the Florida chapter of ETAN and serving as layout editor for Estafeta, its national newsletter. As I organized speaking events, conducted letter-writing campaigns, and spread the word in every way possible, I found myself falling deeply in love with this land I had never seen for myself. I met many people from East Timor; their resilience, intelligence, and commitment to peaceful activism served as a powerful inspiration.

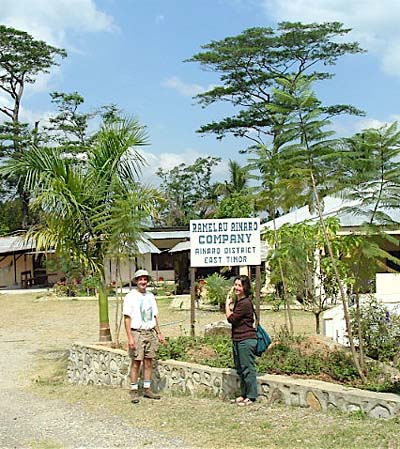

For one reason or another, I never actually went to Timor Loro Sae. College, graduate school, my first years of teaching, scarce finances, dozens of artistic projects, and precious little time away from work all stood in the way for years. Then, this summer, I finally got it together and made the trip. The 2005 delegation of the Madison-Ainaro Sister City Alliance (composed of myself; my lady friend Diane Farsetta, a PR researcher, journalist and radio host; and John Peck, an organizer with Family Farm Defenders, permaculture expert, and fluent Portuguese speaker) left the US on Tuesday, July 19. It would be almost three weeks before I took a shower again.

Part One: With My Own Eyes

East Timor is the poorest nation in Asia, one of the poorest in the world. A great deposit of oil is located in the Timor Gap (to the south), but it will be years before the people will see benefits from that resource; and between scavenging oil corporations and Australia's shady business practices (it refuses to relinquish oil claims it staked during the occupation), it remains unclear just how much the people will benefit from this oil at all.

Of course I knew all of this before our plane touched down at the Nicolau Lobato airport in Dili — but my imagination had been padded by ten years of nothing but glowing reports from friends and colleagues. For whatever reason, I didn't expect East Timor to look like a third world country. Taxiing in from the airport, I was reminded of my first day in São Paulo, Brazil: Plenty of run-down stores, trash in the streets, and kids selling stuff to pedestrians (most of whom ignored them). Dili has no sewage system, so each family's squat toilet feeds into the streetside canal system; the many pigs in town take care of some waste, but there's a lingering odor.

Fortunately, icky is also just skin-deep, and it didn't take long for me to recognize the beautiful core of the land hidden behind the shells of crass commerce and decades of abusive neglect. Yohan and Milena, our gracious hosts in Dili, welcomed us with loving arms into their home, where they were nursing their new baby, Fidelis. (Interesting side note: one of the books I read while in Timor was Dark Rendezvous, a Star Wars novel. It features a droid servant named Fidelis.) The beaches and countryside of the island were every bit as gorgeous as I expected. The craftwork of East Timor — from the traditional tais made by women across the land to the artwork created by the residents of Arte Moris, a cultural center where Yohan works — was a sight to behold. And the quiet dignity of the people was overwhelming.

Fortunately, icky is also just skin-deep, and it didn't take long for me to recognize the beautiful core of the land hidden behind the shells of crass commerce and decades of abusive neglect. Yohan and Milena, our gracious hosts in Dili, welcomed us with loving arms into their home, where they were nursing their new baby, Fidelis. (Interesting side note: one of the books I read while in Timor was Dark Rendezvous, a Star Wars novel. It features a droid servant named Fidelis.) The beaches and countryside of the island were every bit as gorgeous as I expected. The craftwork of East Timor — from the traditional tais made by women across the land to the artwork created by the residents of Arte Moris, a cultural center where Yohan works — was a sight to behold. And the quiet dignity of the people was overwhelming.

I was dumb to have such unwieldy expectations. If absence makes the heart grow fonder, then what do you get by working for a decade in solidarity with a land you've never visited? It's like volunteering for the Narnia Human Rights Coalition. My first few days in Timor were like discovering that your parents are human — it's a letdown from the superheroic pedestal you had them on. But once you get over that nonsense, you can move into an infinitely more rewarding experience relating to them as humans like yourself.

Part Two: Dili, The City

The capital of East Timor is a beachfront mini-metropolis on the north edge of the island. It is oppressively hot and at times feels to be made entirely of concrete. A gentle swarm of taxis and microlets (mini-van buses) roam the streets as people walk along the pseudosidewalks. With 60,000 people (aboiut the same as Janesville, WI or Pensacola, FL), Dili is easily East Timor's largest city — and it shows. In amongst the still- unrebuilt buildings destroyed in 1999 is a struggling but sturdy population trying to make it work with what little they have. Young people from across the country flock to the capital in hopes of finding work, which may or may not exist.

While there are no

official numbers on

unemployment, the lack

of work echoes through

every neighborhood.

Outside the bank downtown, a flock of teenage boys tries to push phone cards to the customers (almost all malae — foreigners, usually white folks). If interest is shown, the vendors begin jockeying for place in line. In the merkadu, older women and kids in the makeshift stalls insist that passers-by really must purchase a tangerine, a bag of coffee, or a live rooster.

While there are no

official numbers on

unemployment, the lack

of work echoes through

every neighborhood.

Outside the bank downtown, a flock of teenage boys tries to push phone cards to the customers (almost all malae — foreigners, usually white folks). If interest is shown, the vendors begin jockeying for place in line. In the merkadu, older women and kids in the makeshift stalls insist that passers-by really must purchase a tangerine, a bag of coffee, or a live rooster.

Diane assured me that the sales pressure was much higher on her last trip (this was her third), but it was still necessary after a point to simply ignore those who wanted my attention. Otherwise, I would raise false hopes and waste my time as well as theirs. There was never a sense of hostility when I walked by, but the intensity of the exchange (one-sided as it was) pointed to a frustration I could only guess at.

A few years back, I was working at Borders bookstore and found it hard to make ends meet. At one point I tried selling an old toaster to a friend; I didn't want to show it, of course, but I really needed him to buy the damn thing — that four bucks would get me food for a few days. Every time a vendor in Dili started in with the sales pitch, I was reminded of that mental state I'd briefly visited. (Of course, I had a generous support network of friends and family who would gladly have loaned me money, had my pride not stood in the way; it both cheered and depressed me to think of others in my shoes without such backup.)

And yet, despite all of the poverty, scraping, and struggle, Dili is host to no beggars. I counted exactly one person with her hand out and a desperately sad look on her face. Everyone else really wants you to buy something — but no one seems interested in getting handouts. (Aside from the "aid" workers from the US and Australia; more on that later.)

East Timor needs what every other poverty-wracked third-world nation needs: access to capital. Infusions of wealth that can rejuvenate communities and pave the way for better lives. In this way, East Timor is no longer unique — its enemy is no longer a monolithic and easily-identified occupying force. But again, I'm getting ahead of myself.

Our friend Yohan had lived in Madison for many years; he was active with assorted community projects and (for a time) the local Timor solidarity group. After independence, he visited East Timor and fell deeply in love with it. He packed his stuff into storage and moved to Dili. He helped to start a performing group called Bibi Bulak (The Crazy Goat) and toured all over the country. Before long, they had their own TV show (one of only a few Timorese-made shows) and played a key role in starting Arte Moris, an artists' community on the edge of town. He fell in love with Milena, a powerful performer with Bibi Bulak, and they were married (in an elongated ceremony worthy of its own detailed storytelling). Two weeks before we arrived, they had a healthy and lovely baby boy.

Our friend Yohan had lived in Madison for many years; he was active with assorted community projects and (for a time) the local Timor solidarity group. After independence, he visited East Timor and fell deeply in love with it. He packed his stuff into storage and moved to Dili. He helped to start a performing group called Bibi Bulak (The Crazy Goat) and toured all over the country. Before long, they had their own TV show (one of only a few Timorese-made shows) and played a key role in starting Arte Moris, an artists' community on the edge of town. He fell in love with Milena, a powerful performer with Bibi Bulak, and they were married (in an elongated ceremony worthy of its own detailed storytelling). Two weeks before we arrived, they had a healthy and lovely baby boy.

Yohan is the first to acknowledge his good fortune — not everyone can pack up shop, move to another country, find funding for a fiercely independent artisan lifestyle, and make a home with a loving family. But Yohan's experience is also rare because his work has always been about telling the unpalatable truth. Bibi Bulak's performances, from the very beginning, worked to expose (among other topics) the hypocrisies and contradictions of the UN administration in East Timor (which ran the country during its rocky transition period). Milena (like the other Bibis) is no different — in the best traditions of Shakespeare, Morrison, and Ridenhour, she uses art to celebrate the best aspects of Timorese life, while confronting its less pleasant aspects (like the pervasive male-dominant culture).

Staying with Milena and Yohan allowed us to see the best of Timorese youth culture — far beyond what you'd see as a tourist in this Small Place. During our week in Dili, they introduced us to family (Milena's uncle regaled us for several hours with his tales of the occupation and Timorese conceptions of the soul) and brought in an endless variety of guests, both Timorese and malae, for a comprehensive view of Dili.

Staying with Milena and Yohan allowed us to see the best of Timorese youth culture — far beyond what you'd see as a tourist in this Small Place. During our week in Dili, they introduced us to family (Milena's uncle regaled us for several hours with his tales of the occupation and Timorese conceptions of the soul) and brought in an endless variety of guests, both Timorese and malae, for a comprehensive view of Dili.

Being a malae in East Timor was an odd experience. White people are the extreme minority (even as they control many powerful entities like the UN offices and US embassy), and this status carries complications. It was the UN who promised to stay with the people of East Timor before the 1999 referendum (and then pulled out when the bloodshed started). It was white folks who set up shop to deliver "aid" when the smoke cleared (and used much of the money to air-condition their offices and pay themselves large salaries).

On a trip to the beach, I listened to a malae named Jeff (an Australian activist with a decent track record of solidarity work) complain about how "There's rubbish everywhere. The Timorese are so lazy. If you're not getting paid for it, you say 'it's not my problem.'" Most of the malaes currently in Timor are men and women from Australia with plenty of money (at least relative to the Timorese). They keep to themselves for the most part, frequenting malae-friendly restaurants and bars, and driving (or taking taxis) to every destination.

As a result, the malae is both a novelty and an opportunity. As we walked the streets of Dili (and Ainaro, where while folks are much more scarce), kids frequently called "Malae!" over and over, even after we smiled and waved and said "Bon dia!" (This gets annoying, even though the kids are just intrigued. After a few days, Diane and I rejoined with "Timor-oan!" which means "Timorese!") Older kids will try some English: "Hello mister. How are you?" But when I replied with: "Very well, thank you. And yourself?" they usually scattered in a fit of giggles.

Being an opportunity is decidedly less pleasant. The American in a poor country gets used to being on his guard (or he'd better, lest he wind up stumbling down the street with every available foodstuff and bauble hanging out of his pockets). But when we were charged $69.00 for one night in a small room with thin little mats over wooden crates (in a land where a taxi ride costs $1.00 and dinner for four rarely tops $15.00), we were so dumbfounded and unsure of what to do that we just paid and fumed.

As devout activists who have dedicated untold hours of work and innumerable Saturdays of organizing to the people of East Timor, we'd hoped that this sort of thing would leave us alone. But I came to realize that — hardcore solidarity comrades or not — someone who is broke and surrounded by limited opportunity will take a shot at whichever mark presents itself, especially if the mark has cash. Ultimately, I can't blame those who scammed us out of a few bucks (certainly balanced out in the big picture by the incredibly low prices for everything else), even if it pissed me off at the time. I can't say I wouldn't do the same thing. At least we'll be ready for it next time.

As devout activists who have dedicated untold hours of work and innumerable Saturdays of organizing to the people of East Timor, we'd hoped that this sort of thing would leave us alone. But I came to realize that — hardcore solidarity comrades or not — someone who is broke and surrounded by limited opportunity will take a shot at whichever mark presents itself, especially if the mark has cash. Ultimately, I can't blame those who scammed us out of a few bucks (certainly balanced out in the big picture by the incredibly low prices for everything else), even if it pissed me off at the time. I can't say I wouldn't do the same thing. At least we'll be ready for it next time.

Besides, I haven't spent ten years of my life working for the liberation of East Timor because I thought it would get me street cred. The corollary here is: If it did get me said cred, I doubt I'd want it. (After all, we didn't go around trumpeting our years of commitment to the people. We brought it up when it was relevant, which wasn't often.)

For me, it became a matter of remembering why I was there, and simply being careful with (or, when necessary, abandoning) the rest. An indigenous activist named Lilla Watson famously said: "If you've come here to help me, you're wasting your time. But if you've come here because your liberation is bound up with mine, let us work together."

As for home life, the biggest change I had to acclimate to was the mandi. Indoor plumbing is a pipe dream in most of Timor (sorry for the pun), and hot water comes only from a pot atop a stove (or, often, a fire). Ergo, bathing is achieved with a plastic scoop and a huge tank of cold water. Having a mandi after walking around in the Dili heat is the closest I've ever come to understanding the allure of masochist behavior: the pain was intense, but it felt wonderful.

Beside the mandi is the squat toilet; the same plastic scoop is used to "flush" waste away. My body didn't want to accept the squatting position at first, but after a few days I got totally used to it and (aside from a time when I thought I had no toilet paper) eventually came to prefer it. I'd read somewhere that our usual sit-toilets are less healthy; either way, it became no big deal.

In his fascinating book A Geography of Time, Robert Levine explores the psychosocial impact of the hurried pace in larger industrialized cities (Tokyo, New York) compared to the more leisurely tempo of other places (Mexico City, Rio De Janeiro). His research found that incidence of heart disease is higher among the "faster" cities, as is the degree to which residents feel satisfied with their lives. (This has much to do with wealth, as Levine points out; faster cities tend to be more economically productive. But I also wonder if those of us living in a rat-race society more deeply appreciate our downtime, since we have less of it? Then again, our wealth allows us more options on how to make the most of that downtime.)

I couldn't stop thinking about all of this while in Timor. Most people operate on event time, even though watches and clocks are ubiquitous. Friends came by "in a little while," and the schedule of the market revolved around customers, not the other way around. When we met with folks from Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), the discussion always took several minutes to amble toward the main focus. Indeed, when we met late in the trip with a gentleman from Burma, he was so direct and pointed ("What can I do for you?" he asked explicitly, once we had moved into his office) that I was surprised and a little disoriented.

I couldn't stop thinking about all of this while in Timor. Most people operate on event time, even though watches and clocks are ubiquitous. Friends came by "in a little while," and the schedule of the market revolved around customers, not the other way around. When we met with folks from Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), the discussion always took several minutes to amble toward the main focus. Indeed, when we met late in the trip with a gentleman from Burma, he was so direct and pointed ("What can I do for you?" he asked explicitly, once we had moved into his office) that I was surprised and a little disoriented.

This was most of our first week: meetings, discussions, trips to the merkadu, reading. A tropical vacation. Sadly, I was so overcome by the enormity of the new problems facing East Timor that I felt like a tourist. Back home, I can raise funds, teach the youth, make websites, and write letters. But in Timor all I could really do was look, listen, and learn. Clearly these are prerequisites for action; but after several days I began to ache for something concrete. I wanted to help dig a drainage ditch or teach a class. Instead, I drank coffee and took pictures.

Eventually, we'd done all we'd come to do in Dili and it was time to move up into the mountains. We hired a truck and Chris, our amiable driver, took us south to Ainaro.

Part Three: Ainaro (The Past Didn't Go Anywhere)

Elvis Ferreira lives across the street from the old Portuguese hospital in Ainaro. Unfortunately, he can't go there for medical help — militia groups armed by Indonesia burned the hospital to the ground in 1999, and there are no plans to rebuild it. Today, a charred husk of concrete reminds us of the wretched destruction that the world watched idly, unwilling to pressure Indonesia

because that might hurt business relations. Trees grow through what were once patient rooms; the aqua cross and a painting of Jesus are among the only signs of the building's purpose.

Elvis Ferreira lives across the street from the old Portuguese hospital in Ainaro. Unfortunately, he can't go there for medical help — militia groups armed by Indonesia burned the hospital to the ground in 1999, and there are no plans to rebuild it. Today, a charred husk of concrete reminds us of the wretched destruction that the world watched idly, unwilling to pressure Indonesia

because that might hurt business relations. Trees grow through what were once patient rooms; the aqua cross and a painting of Jesus are among the only signs of the building's purpose.

Of course, if we call too much attention to these events, someone is likely to accuse us of living in the past. A pundit sitting in the chair left to him by his father in a house made possible by a sizeable inheritance, wearing an American flag to commemorate 9/11, will — without a hint of irony — insist that people wounded by history need to move ahead and forgive past crimes.

This is one reason why East Timor's leaders are not calling for an international tribunal to prosecute the crimes of 1999 (and before). Passionate about building good diplomatic and economic relations with their former occupiers, many heads of the Timorese state are ignoring the plea for justice coming from every sector of their nation. This is causing serious disappointment and (I imagine) severe disenchantment among many Timorese. Truth commissions are powerful and important, but imagine how hard it would have been for Germany and the Jews of Europe (along with the gypsies, homosexuals, and others murdered) to press on had there been no Nuremberg trials.

Naturally, Elvis — like everyone in East Timor — isn't just waiting around for justice to arrive. He is the coordinator for Centro Moris Foun, a community group which conducts trainings on woodcraft, engine repair, and agriculture. The CMF has opened a small workshop which offers a variety of services, and it serves as an important organization in this quiet town.

Naturally, Elvis — like everyone in East Timor — isn't just waiting around for justice to arrive. He is the coordinator for Centro Moris Foun, a community group which conducts trainings on woodcraft, engine repair, and agriculture. The CMF has opened a small workshop which offers a variety of services, and it serves as an important organization in this quiet town.

Although it is the capital of the district of the same name (the district is home to around 54,000 people), Ainaro is a small village which can be crossed on foot in an hour. The people are relaxed and friendly; on our first day, we visited the police station in search of our friend Valentin Soares; the officers smiled and pointed us to a female officer who, we quickly realized, was his wife. She introduced herself and called him on her mobile phone. (Land lines don't really exist in Timor. Everyone works with mobile phone numbers and — more out of economy than novelty — text messaging.)

Valentin has been a solid partner of the Madison-Ainaro Sister City Alliance since it began, and he made it his business to arrange meetings for us with government officials and community leaders. Since he has a family and a construction job as well (in addition to serving as the coordinator of the Centro Communidade and working to fix his truck), he wasn't always available to serve as guide and translator; but he endeavored to prove that he valued our work and wanted to help our relationship prosper as a real friendship between communities. Valentin is one of the warmest people we met in Timor, and his kindness is matched only by his indefatigable sense of humor.

Other women and men in Ainaro are just as committed. We met with Senora Carlotta, the coordinator of OPMT, a local women's group; reporters and engineers at the community radio station, Lian Tatamailau; and Alexandre de Aurago, the District Superintendent of Education. They told us how they use the scarce resources to which they have access, and what they most desperately need to serve the community. With our slight bundle of delegation funds, we distributed a

number of mini-grants to various organizations. Sadly, we never felt it was enough; but we had no doubt that the people in these groups would make the most of what little we had to offer.

Other women and men in Ainaro are just as committed. We met with Senora Carlotta, the coordinator of OPMT, a local women's group; reporters and engineers at the community radio station, Lian Tatamailau; and Alexandre de Aurago, the District Superintendent of Education. They told us how they use the scarce resources to which they have access, and what they most desperately need to serve the community. With our slight bundle of delegation funds, we distributed a

number of mini-grants to various organizations. Sadly, we never felt it was enough; but we had no doubt that the people in these groups would make the most of what little we had to offer.

As malaes with access to funding, we sometimes felt unsure of what we were told. One school's headmaster told us their top priority was not hiring more teachers (they have three paid educators and 14 volunteers), but $9,000 for a fence around the campus. And while the radio station kept meticulous records from our last mini-grant, there were questions about some of their bookkeeping practices. Still, these experiences were extremely rare, and are certainly on par with (or below) shadiness to be found in NGOs around the world.

Our visit to Timor took place in the late summer, when school has just finished. Thus, I was unable to visit a class in session; and as I listened to Mr. Aurago describe the status of the

district, I had severe trouble imagining myself in such a situation. The district has two secondary schools (what we call high school in the US), and only ten permanent secondary teachers on staff (all others are volunteers). Most classes in the primary and secondary grades have 40-50 students for each teacher. Many schools have no desks and few resources for chalk, equipment, or books. Even the district office lacks a computer. Because the

government must charge school fees, many families cannot afford (or choose not to prioritize) school for their children. (Girls are excluded disproportionately from education.) In the rural areas of Ainaro District, less than 25% of the kids go to school.

Our visit to Timor took place in the late summer, when school has just finished. Thus, I was unable to visit a class in session; and as I listened to Mr. Aurago describe the status of the

district, I had severe trouble imagining myself in such a situation. The district has two secondary schools (what we call high school in the US), and only ten permanent secondary teachers on staff (all others are volunteers). Most classes in the primary and secondary grades have 40-50 students for each teacher. Many schools have no desks and few resources for chalk, equipment, or books. Even the district office lacks a computer. Because the

government must charge school fees, many families cannot afford (or choose not to prioritize) school for their children. (Girls are excluded disproportionately from education.) In the rural areas of Ainaro District, less than 25% of the kids go to school.

As an added confusion, the national government has mandated that Portuguese, the official language of East Timor, must be used for instruction in primary schools. Since most Timorese speak only Tetun (or some other indigenous language), this has been a frustrating experience for everyone involved. In the coming school year, teachers in pre-secondary schools are being required to teach in Portuguese, even though few (if any) speak it.

Only a small portion of the population speaks Portuguese, most of them older folks who were around in the time of Portugal's colonial reign. Many younger men and women we spoke to advocate the use of Tetum in the schools; or even English, as it's becoming valuable as a marketable skill for workers to have.

Hearing about these regulations and conditions, I began to think about my own situation as a teacher in the US. I encourage any teacher who may read these words to imagine as I did: You probably think of 30 students as a large class. Now Imagine you have 45, and no desks for anyone (maybe a small table for yourself). You have no books (nearly impossible for me to conceive, as an English teacher), and if the students have paper, it's scarce. The school has no computers or copy machines. And of course, remember that many teachers in Ainaro don't get paid.

I was relieved to hear that the administrators in Ainaro had been classroom teachers for many years. When I told Valentin that teachers in the US frequently work under administrators who have never been in the classroom, he looked puzzled. "How do they know how to work with people in the classes?" he asked.

I shrugged. "Sometimes they don't," I said.

One of the two secondary schools in Ainaro District is run by the Catholic Church, easily the most visible institution in the community. The church itself is a pillar of the village, standing high on the hill and attracting the devout from around the region. The Sunday mass we attended (one of two that day) packed the pews, but it was something of a disappointment to Padre Francisco Tavares dos Reis, a gentle and congenial man who had served as a guerrilla in the mountains during the occupation.

One of the two secondary schools in Ainaro District is run by the Catholic Church, easily the most visible institution in the community. The church itself is a pillar of the village, standing high on the hill and attracting the devout from around the region. The Sunday mass we attended (one of two that day) packed the pews, but it was something of a disappointment to Padre Francisco Tavares dos Reis, a gentle and congenial man who had served as a guerrilla in the mountains during the occupation.

Father dos Reis was saddened by the relatively low turnout in church, explained by young peoples' attractions to less godly pursuits like soccer, rock music, and relaxing with friends. He recognized that the problem is not unique to Ainaro, but we didn't have the heart to tell him that we weren't big church patrons back home either. We didn't feel ready to explain our disenchantment with the outmoded orthodoxy of contemporary religious institutions relying on centuries-old texts and arbitrary interpretations of same. Instead we just nodded and agreed that there was indeed something wrong with These Young People Today.

Fortunately, our discussion focused not on theology but on the conditions of life in Ainaro. Father dos Reis described the conditions in the church schools (better than in the public schools, but not by much) and the problems of folks in even smaller towns like Cassa, to the south. During the last harvest, many families had trouble finding enough to eat, and efforts were underway to prevent a repeat of this problem in the coming months.

While the church doesn't rely as closely on external support as the NGOs do, it is an integral part of the economy, and can therefore sense the fiscal health of the region. As we found out, the news isn't good. Part of the problem is that the UN recently withdrew from many areas of East Timor, as the mandate for the transition administration had ended. Sadly, the UN had failed to implement much of the capacity-building and long-term production it promised. Worse, we heard many stories of UN personnel taking computers and other equipment with them, after having spent years training the Timorese on how to use them. (As John Peck pointed out, it probably cost the UN as much to ship it out as it would to buy new machines.)

I don't want to present the UN missions in East Timor as total failures; indeed — like most Timorese solidarity activists — I am a proud

supporter of the United Nations. It was the UN, after all, which administered the referendum on independence; and the UN often serves as an important force for diplomacy among world bodies which would otherwise reach immediately for the saber. (Granted, the UN has also served as a proxy saber itself — an issue for another time.) There's no doubt that the foreign UN workers (and World Bank personnel, and other large NGOs) came to East Timor with good intentions. Furthermore, the UN has done some important work in East Timor, from coordinating the peacekeeper team which finally drove the Indonesian military out, to providing invaluable assistance to the fledgling government.

I don't want to present the UN missions in East Timor as total failures; indeed — like most Timorese solidarity activists — I am a proud

supporter of the United Nations. It was the UN, after all, which administered the referendum on independence; and the UN often serves as an important force for diplomacy among world bodies which would otherwise reach immediately for the saber. (Granted, the UN has also served as a proxy saber itself — an issue for another time.) There's no doubt that the foreign UN workers (and World Bank personnel, and other large NGOs) came to East Timor with good intentions. Furthermore, the UN has done some important work in East Timor, from coordinating the peacekeeper team which finally drove the Indonesian military out, to providing invaluable assistance to the fledgling government.

But as we know from history, the UN is only as strong as the nations which compose it (and the powerful nations which steer its course). And in East Timor, it has only been as strong as the connections it has made to the people of this new nation. Sad to say, these have been minimal. The Timorese reconstruction- and development-monitoring organization La'o Hamutuk has documented numerous instances where UN policies and practices have failed to provide for the needs of East Timor. For instance, instead of providing a comprehensive overhaul of Dili's water supply, the UN Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET) spent $4 million each year to provide itself with bottled water. And when civil unrest broke out in 2002, the UN police forces were unprepared to handle the situation, despite years of training exercises and millions of dollars spent.

All of this is endemic of what many in the solidarity community are calling the "reconstruction industry": a consortium of advisers, experts, technicians, and bureaucrats who move from place to war-torn place, assessing damage, offering aid, and making a comfortable living in the process. Naturally, these men and women expect only the best for themselves; in Dili, a huge ship called the Hotel Olympia was set up opposite the UNTAET building to provide foreign workers with the comfort to which they're used. This was made possible by salaries for foreign workers about 50 times higher than Timorese doing the same work. It's little wonder that "Well-Paid Wankers" (which bluntly challenges the legitimacy of such economic disparities) has been one of Bibi Bulak's most popular songs.

Even when aid money does make it into the local economy, people in the third world are often victims of a shell game. The IMF is notorious for forcing governments to cut social programs while increasing their export systems. And aid packages from wealthy nations often serve to do little more than ready terrain for corporate profit extraction. (For more on these issues, see my articles Global Economics 101: Five Things Everyone Should Know About the IMF, World Bank, and WTO and Global Economics 201: Five More Things Everyone Should Know About International Economics and "Free Trade".)

Even when aid money does make it into the local economy, people in the third world are often victims of a shell game. The IMF is notorious for forcing governments to cut social programs while increasing their export systems. And aid packages from wealthy nations often serve to do little more than ready terrain for corporate profit extraction. (For more on these issues, see my articles Global Economics 101: Five Things Everyone Should Know About the IMF, World Bank, and WTO and Global Economics 201: Five More Things Everyone Should Know About International Economics and "Free Trade".)

All of these global economic matters trickle down in their own way to Ainaro. Vendors in the market who used to be able to break a $10 bill now provide merely a helpless look in exchange for anything more than $1. (The US dollar is the official currency in East Timor.) The Centro Communidade has had to cancel many programs because of slashed funding. And one of only four restaurants in town had closed since our group's last trip, due to slow business. (The others served little vegetarian fare aside from mie goreng, better known to Americans as ramen noodles. I ate enough of these noodles in one week to last me several years.)

In light of these massive matters of international finance, our mini-grants felt like drops in the ocean; but we believed it was money well spent, because we trusted the people receiving it. Having finished what we set out to achieve in Ainaro, our notebooks packed with information and our cameras filled with photos, we headed back to Dili.

The roads between Dili and Ainaro are twisty and bumpy, with large stretches of unpaved rock along the way. They're just wide enough to barely fit one vehicle beside another, so passing is done with care. On the way up from Dili, our driver, Chris, honked the horn as he took us into each turn; on more than one occasion we stopped suddenly and slid over to let a truck or bus proceed in the other direction. I was nervous for some of the trip, but the Japanese government has been doing good work helping to pave the roads, and Chris was very skilled behind the wheel.

On the way back to Dili, we were met at 7:00 AM by a bus packed completely full of people. Valentin had secured us three seats toward the back, so we begged our way past a gaggle of people crouched in the aisle and cramped three to a bench. Several burly guys hurled our bags up top, and we set out for the capital. Although there was some room in the bus (even as we picked up passenger after passenger, despite my belief that we were already at capacity), many young men chose to ride in the doorway, sometimes holding onto nothing more than a small bit of the wall. One of these, a fellow we came to call Shawl-Man, had a wondrous knack for clambering around the edges of the vehicle. At one point, we watched (and listened, when he was out of sight) as he made his way from the rear door, onto the ladder in back, over the roof, and down into the front doorway — all while simultaneously keeping his cigarette lit and maintaining the green shawl wrapped around his head and shoulders.

On the way back to Dili, we were met at 7:00 AM by a bus packed completely full of people. Valentin had secured us three seats toward the back, so we begged our way past a gaggle of people crouched in the aisle and cramped three to a bench. Several burly guys hurled our bags up top, and we set out for the capital. Although there was some room in the bus (even as we picked up passenger after passenger, despite my belief that we were already at capacity), many young men chose to ride in the doorway, sometimes holding onto nothing more than a small bit of the wall. One of these, a fellow we came to call Shawl-Man, had a wondrous knack for clambering around the edges of the vehicle. At one point, we watched (and listened, when he was out of sight) as he made his way from the rear door, onto the ladder in back, over the roof, and down into the front doorway — all while simultaneously keeping his cigarette lit and maintaining the green shawl wrapped around his head and shoulders.

Back in Dili, we spent some more time in meetings, and I met with some folks at the Bairo Pite Clinic, where Dr. Dan Murphy (a native of Iowa) has spent years providing free health care for the people. After I mentioned my ability to design and update websites, they enlisted my services and provided me with information I would need to help the current webhost. We met more friends of Yohan and Milena, and spent a few final days with the baby before we took off once more for The States.

Part Four: The Seoul Interlude (A Dream of Baduk Deferred)

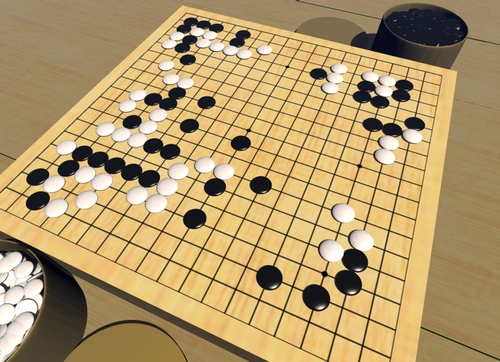

The flight at the start of our journey from Chicago to Seoul, South Korea was 13 hours long. (This was followed by another six-hour flight from Seoul to Denpasar, Bali; and one three-hour flight from Denpasar to Dili.) I was unsure of how I'd fill the time, until I remembered that Korea was a land where my favorite game, Go (they call it Baduk), is enjoyed by millions of people. We were flying on Korean Air.

I mentioned this to my friend Dave, who nodded and explained how he had made a little sign for his flight to Japan; he'd found someone immediately and passed the flight in the blink of an eye, playing for hours on a magnetic board. I prepared myself for a similar good time. I purchased a travel set and made a sign of my own (in Korean, of course). I was bursting with excitement by the time we boarded.

I mentioned this to my friend Dave, who nodded and explained how he had made a little sign for his flight to Japan; he'd found someone immediately and passed the flight in the blink of an eye, playing for hours on a magnetic board. I prepared myself for a similar good time. I purchased a travel set and made a sign of my own (in Korean, of course). I was bursting with excitement by the time we boarded.

I got the set out once we were in the air, but the only one around me who looked interested was a young man to my right who was mildly interested but had never learned. So I showed him the ropes, and of course it was just like teaching anyone — he took a long time to make his moves, and I was more than a little bored. By the time I was ready to walk the aisle with my sign, they were passing out food; then came the movie, when the whole cabin was dark. Several hours later, I gave it a try; but the only person who spoke to me gave a puzzled look and said: "What's that?"

I was sad by the time we reached Seoul, but when I found the elaborate baduk section in the airport bookstore, my heart cheered. (Many baduk books don't require the reader to speak the language; the diagrams are easy to understand, even if the writing is unintelligible.) I tried again on the shorter flight, but by then there were even fewer Koreans on the plane, and none of them gave me a second look. Diane and I played once in Timor, but no one else showed much interest (for which I was grateful, as explaining the rules in my fractured Tetun would have been agonizing).

I had abandoned my sign efforts when we landed in Denpasar on our way back home, but as we ate dinner in a superb relaxed spot called Aromas (look it up if you ever go there), we reviewed our remaining flight schedule and made an intriguing discovery: what we had thought was a half-hour layover in Seoul was in fact a twenty-four and a half hour layover. This would give me time to visit the city and find one of the many baduk parlors I'd heard so much about.

Only it didn't quite work out the way I'd hoped. We spent an hour at the airport information desk (where a very nice lady provided information about the Korean Baduk Association), and then two hours trying to find the hostel where we would be staying. By the time we were settled, it was almost time for the KBA to close. Still determined, however, Diane and I jumped into a taxi and headed for the address.

When we arrived, I felt like Malcolm in Mecca. We made it! The building had an enormous mural of two children playing Baduk in the grass. Finally, I would meet up with my people. Only they weren't around.

When we arrived, I felt like Malcolm in Mecca. We made it! The building had an enormous mural of two children playing Baduk in the grass. Finally, I would meet up with my people. Only they weren't around.

The lobby contained a gift shop and a security guard. He told me, with hesitant English and many hand gestures, that there was a studio on the second floor (I had seen some clips from Baduk TV online, but I wanted to play), and an office on the third floor. We went up to the office in the hopes of finding information on parlors, but we found only an office. It looked like every run-of-the-mill corporate cubicle farm you've ever seen.

Eventually we attracted the attention of one of the bored denizens, who explained that he couldn't help us; that it was just a place for professional players. I asked if maybe he could point me to anywhere that might offer me a game; he retreated into a cubicle and came back twenty minutes later with a printed webpage advertising (in Korean) a baduk training centre. As we thanked him, he cautioned us that we probably couldn't play there, either, since it was only for students wishing to become pros.

Directions in Seoul, as we had found in the hunt for the hostel, were excruciatingly vague. As we tried to interpret the map for the training centre, we squinted at street names and flipped the page around. Thirty minutes later, it looked hopeless. Then it started to rain. Irritated, tired, and saddened, we took one last chance by stepping into a pharmacist's shop. We held up the paper and said "Do you know this place?" He read it carefully, then made a noncommittal gesture toward the alleyway. (Many businesses in Seoul — including out hostel — reside at the end of tiny alleys.)

As we continued walking, I scanned the ubiquitous Korean writing for the three characters I did recognize — the ones for Baduk on the sign I'd made for the plane. Then, finally, I saw them on a second-story storefront. We dashed up the stairs and I grinned foolishly as I beheld a room right out of Hikaru no Go: Seven tables full of kids, their shoes traded for slippers, playing Baduk.

The director of the center, Heo Ki Cheal, welcomed us and gave us a painfully tart lemon energy drink. I explained my situation and said I was ranked 8k on the Kiseido Go Server. He nodded and returned a minute later with an eight-year-old girl. "She is training to be a professional," he said. "She's about your level." The girl, smiling wildly, bowed repeatedly.

Needless to say, she crushed me. In my defense, I was exhausted (I can never sleep on planes) and agitated from the day's confusion. I tried to strong-arm my way around the board, stretching across her framework and leaving my positions undefended. She calmly responded with precision, and before I knew it, I had to resign.

Needless to say, she crushed me. In my defense, I was exhausted (I can never sleep on planes) and agitated from the day's confusion. I tried to strong-arm my way around the board, stretching across her framework and leaving my positions undefended. She calmly responded with precision, and before I knew it, I had to resign.

But it didn't matter. I had reached my goal — we'd played a game. And that was enough to send me back to the States with a goofy smile on my face and a long, boring story to write about.

Afterwards, we reviewed the game; the girl (and her mentor, who apparently is the sister of a major Korean champion of the moment) showed me my various mistakes (many of which I was aware of three seconds after I'd made the moves). This was tricky, since she spoke no English and I spoke no Korean — but through a lot of nodding and hand gestures, we made it work.

At one point, she showed me how I could have killed one of her groups. Placing the final stone, she demonstrated that the group would die by crossing her eyes, sticking out her tongue, and clutching her throat in a comical faux-choking action. It was the perfect end to a maddening day.

Part Five: Conclusions

My trip to East Timor was at once a glorious and life-affirming journey ten years in the making, and the disappointing culmination of something I had spent my entire adult life working toward. While of course I must base my impressions of pre-independence Timor on a multitude of second-hand accounts, there appeared to me a sense that the present is not the future it once was.

During the occupation, the people of Timor Loro Sae were reaching for a place in the world; trying to get out from under the boots to the place where everyone else was. Maybe they did realize — or maybe it was hard to see — that the place where everyone else was (okay, 95% of the world's population) ain't no crystal stair.

During the occupation, the people of Timor Loro Sae were reaching for a place in the world; trying to get out from under the boots to the place where everyone else was. Maybe they did realize — or maybe it was hard to see — that the place where everyone else was (okay, 95% of the world's population) ain't no crystal stair.

When East Timor regained its independence, I remember telling folks (everyone was asking "What now?") that there would be an effort to turn the new nation into the Haiti of southeast Asia (or another Haiti, I should say). Unfortunately, it looks like I was right. Neoliberal economic institutions like the IMF are trying to force the government of East Timor to open itself up to labor exploitation in the name of "free trade," and Australia's shady oil dealings could fill volumes. While the government's commitment to keep itself debt-free is a very positive sign (especially given Jamaica's problems with the institutions of global usury), the World Bank seems relentless in its attempts to convince Timorese leaders that they have nothing to fear.

These are complicated matters; I don't want to oversimplify the situation. (Just like local and state governments in the US, officials in Timor must balance the need for jobs and wealth with the need for responsible economic practices.) But given the massive distortions of power on the worldwide financial stage, the future doesn't look very bright for the people of East Timor.

It's not as bad as life under the occupation, of course. The Timorese would no sooner want that life back than the average Iraqi would want Saddam back in power — or black sharecroppers in the early 1900s would want a return to actual slavery. But we (all of us, regardless of our status) must recognize that our fondness for ranking of relative suffering is of (at best) marginal importance. And the refusal of many in the wealthy nations to acknowledge (and/or the unwillingness to take action against) the presence of desperate conditions — even if they are an improvement over other, more desperate, conditions — is a disgrace to the notion of human evolution, and a mark of shame on our species.

Above all else, it is necessary for us as people who position ourselves on the side of good (or God, or freedom, or democracy, or whatever you like to call it) to finally admit that the moderate, gelatinous tiptoes toward better living for the majority of humankind — steps descended from genocide, slavery, colonialism, and racism (and without significant changes to either the institutional structures of those primitive globalizations or the direction of their wealth flow) — must be abolished in favor of something(s) more fundamentally just.

It's also necessary for us to recognize that this poverty and suffering exists right beside us, even in the heart of the empire. Schools in Harlem suffer from conditions that look alarmingly similar to those in Ainaro. Black unemployment continues to rise even in the midst of our current "economic recovery". Underground economies like drug-dealing which don't (yet?) exist in East Timor deal a double blow of hope and despair to those suffering from the worst of times.

And I find myself in the midst of it all, one person who just wants to do right. I learned long ago that I can do more — much more — when I work with groups of like-minded people. But I doubt I'll ever be able to resolve the question of how best to achieve these goals that seem so very far away.

As with any large system of human interaction, there are serious questions about the best place to work and/or apply pressure. Should we operate inside the system, or outside? As one of five people in Madison working to raise a few thousand bucks for tiny groups in Ainaro, I feel sometimes like I'm rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic. (Thanks to Utah Phillips for the metaphor.) But if I were working in the UN, wouldn't I feel like part of the problem? There are never easy answers to these questions; in the end, the only certainty I've come to is that our work in East Timor isn't finished. (It may never be.)

Those of us who work in solidarity with the people of East Timor are not blind idealists or naive hippies. (During the occupation, we were called these names and worse, as the cynics of the world tried to convince us that Indonesia's annexation was a done deal and that we should accept realpolitik. Now we get to say: "Ha, ha! You were wrong. Told you so.")

Those of us who work in solidarity with the people of East Timor are not blind idealists or naive hippies. (During the occupation, we were called these names and worse, as the cynics of the world tried to convince us that Indonesia's annexation was a done deal and that we should accept realpolitik. Now we get to say: "Ha, ha! You were wrong. Told you so.")

We do not stage protests just to have a good time (although we often do). We raise our voices — we demonstrate, we lobby Congress, we write letters, we host fundraisers, we make speeches — because the people of East Timor deserve nothing less than full justice for their decades of suffering, made possible by support from the US government.

We speak out because we want to live in a world based not on greed and the obliteration of history; but on human needs, equality, democracy, and justice. We want everyone to have food, housing, medical care, and a decent standard of living. In a world as wealthy and bountiful as ours, there is no reason for caring people to accept the suffering that exists all around us, even in a place so far away and unknown to America as East Timor.

A luta continua: The struggle goes on.